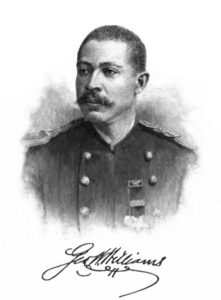

George Washington Williams was born on October 16, 1849, to Thomas and Ellen Rouse Williams in Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania. A year after his birth, Williams moved with his family to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where Thomas secured a job working on Pennsylvania canals. He soon fell into drinking and Ellen decided to move the family to Newcastle, Pennsylvania. Later, a sober Thomas moved to Newcastle to be with them, where he became a minister and a barber.

George Washington Williams was born on October 16, 1849, to Thomas and Ellen Rouse Williams in Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania. A year after his birth, Williams moved with his family to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where Thomas secured a job working on Pennsylvania canals. He soon fell into drinking and Ellen decided to move the family to Newcastle, Pennsylvania. Later, a sober Thomas moved to Newcastle to be with them, where he became a minister and a barber.

Williams’ father was not concerned with his education and thought his son was becoming increasingly rebellious as a teenager. His parents placed him in a refuge house for undisciplined and unruly children that taught adolescents specific trades. It is assumed that Williams was sent there to become a barber. At the age of fourteen, however, Williams enlisted in the Union army to fight in the Civil War. Too young to meet the age requirements, he used false names. The names he registered under are not known for sure, but he is thought to have used the name William or Charles Steward. After the war had come to an end, Williams, thirsty for adventure, enlisted in the Mexican army to help the Mexicans fight the French colonists. He later enlisted in the United States army in 1867, serving only a year. His military experiences would later prove to be influential in creating such works as The Ethics of War, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, and The Constitutional Results of the War of the Rebellion.

Religion also influenced Williams’ writing. After moving to St. Louis in 1868, his interest in the ministry began to grow. Although he had minimal if any academic training, he was able to enter the Newton Theological Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1870. While in school, Williams attended the Twelfth Street Baptist

Religion also influenced Williams’ writing. After moving to St. Louis in 1868, his interest in the ministry began to grow. Although he had minimal if any academic training, he was able to enter the Newton Theological Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1870. While in school, Williams attended the Twelfth Street Baptist

Church in Boston for which he eventually served as pastor and later wrote an 80-page history. A little over a year later he moved to Washington, DC and started a newspaper called The Commoner, directed to the African-American community. Other prominent African-Americans in the community, such as Frederick Douglass, funded the paper. In 1876, Williams gave up the paper to return to religion. He moved to Cincinnati, Ohio and became the pastor of the Union Baptist Church. Religion always seeped into Williams’ writing. Williams addresses religion in various sections of his History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880.

In Cincinnati, Williams began to show interest in politics. Williams, a republican, ran for a seat on the Ohio legislature in 1877, but lost. However, in 1879 he ran again for the position and became the first African-American to serve in the Ohio legislature. He did encounter racism, and what popularity he did have from African-Americans quickly vanished in 1880 when Williams attempted to pass a bill regarding cemeteries in order to remedy the complaints of several wealthy citizens of Avondale, Ohio. Williams proposed that anyone living within a half- mile from the Colored American Cemetery could petition the Board of Health if they were convinced that the cemetery was a hindrance. In turn they could prohibit any more burials in that particular cemetery. Many people in the black community became enraged that he was assisting the wealthy white community to the detriment of the African-American community. His political career ended around this time, after having served only a year.

In 1883, shortly after his career as a politician, Williams’ History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers, and as Citizens was published. He had worked on the piece for seven years. In order to produce this historical account, Williams studied over 12,000 books, a thousand of which are mentioned in his historical account. It consists of two volumes, nine parts, and 60 chapters. It was perhaps one of the most definitive and extensive works chronicling the early life of African-Americans. It was this work that made him a person of recognition.

In 1885, President Chester Arthur took notice and appointed Williams to be a U.S. ambassador to Haiti, but he never took the position, because the following administration canceled it. His world travels, however, continued when, on a trip in Europe, he made the acquaintance of King Leopold of Belgium. The king sparked an interest in Williams for the Congo in Africa. He was later to make several visits there, and much to the dismay of the king, S.S. McClure, a well-known editor and publisher at the time, commissioned him to write articles on the treatment of the natives under Belgian rule. In 1890, Williams published two articles on Belgian rule in the Congo: An Open letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo and A Report Upon the Congo-State and Country to the President of the Republic of the United States.

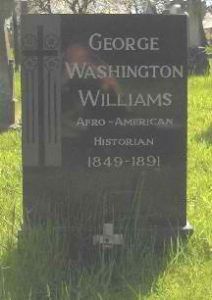

Williams later traveled to other colonies in Africa controlled by Great Britain, Portugal and Egypt. Unfortunately, when he returned to England in the summer of 1891, he fell ill with tuberculosis and pleurisy. Williams died in Blackpool, England on the second of August at the age of 42. He left behind his wife, Sarah Sterett Williams, whom he had married 17 years earlier, and one son.

References and Suggested reading:

George Washington Williams. Penn State University Libraries.16 Jul 2012

http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Williams__George_Washington.html

George Washington Williams.2012 Wikipedia. 16 Jul 2012

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington_Williams

George Washington Williams.2005 African American Legislators. 16 Jul 2012

http://www.georgewashingtonwilliams.org/Legislators.aspx?letter=W&publicOfficialId=89