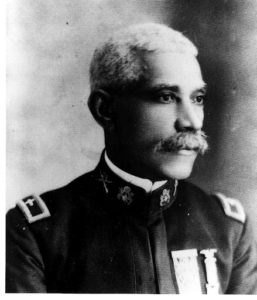

Allen Allensworth was born a slave in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1842. At the age of 12, he was “sold down river” for trying to learn to read and write. After some trading by slave dealers, he was taken to New Orleans, and bought by a slaveholder to become a jockey. The Civil War started, and when the Union forces neared Louisville, Allensworth found his chance for freedom. He joined the Navy and when he was discharged, he had achieved the rank of first class petty officer. In 1871, he was ordained as a Baptist minister and entered the Baptist Theological Institute at Nashville. While serving at the Union Baptist Church in Cincinnati, he learned of the need for African American chaplains in the armed services, and got an appointment as Chaplain of the 24th Infantry.

Allen Allensworth was born a slave in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1842. At the age of 12, he was “sold down river” for trying to learn to read and write. After some trading by slave dealers, he was taken to New Orleans, and bought by a slaveholder to become a jockey. The Civil War started, and when the Union forces neared Louisville, Allensworth found his chance for freedom. He joined the Navy and when he was discharged, he had achieved the rank of first class petty officer. In 1871, he was ordained as a Baptist minister and entered the Baptist Theological Institute at Nashville. While serving at the Union Baptist Church in Cincinnati, he learned of the need for African American chaplains in the armed services, and got an appointment as Chaplain of the 24th Infantry.

He had seen many African Americans move west after the Civil War to escape discrimination. With four other men with similar vision, Allensworth decided to establish a place where African Americans could live and thrive without oppression. On June 30, 1908, they formed the California Colony Home Promoting Association. They selected an area in Tulare County because it was fertile, there was plenty of water, and the land was available and inexpensive. They first bought 20 acres, and later, 80 more. The little town with a big vision grew rapidly for several years — to more than 200 inhabitants, by 1914. That same year Allensworth became a voting precinct and a judicial district. Colonel Allensworth was killed on September 14, 1914, when hit by a motorcycle, while getting off a streetcar in Monrovia. After a funeral at the Second Baptist Church in Los Angeles, he was buried with full military honors.

Since most of the water for Allensworth farming had to come underground from the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and there were many other farms and communities between the mountains and Allensworth, the water supply for the town and farms began to dry up. The next blow was the Great Depression that hit the whole country in the early 1930s. Public services began to shut down, and many residents moved to the cities to look for work. The Post Office closed in 1931. By the 1940s, most of the residents were migratory farm workers, and the population was mainly a mixture of Blacks and Hispanics. Housing deteriorated, as most of the people didn’t consider Allensworth their permanent home. The population had shrunk to 90, in 1972, and later dropped to almost zero.

Since most of the water for Allensworth farming had to come underground from the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and there were many other farms and communities between the mountains and Allensworth, the water supply for the town and farms began to dry up. The next blow was the Great Depression that hit the whole country in the early 1930s. Public services began to shut down, and many residents moved to the cities to look for work. The Post Office closed in 1931. By the 1940s, most of the residents were migratory farm workers, and the population was mainly a mixture of Blacks and Hispanics. Housing deteriorated, as most of the people didn’t consider Allensworth their permanent home. The population had shrunk to 90, in 1972, and later dropped to almost zero.

A drive began in the early 1970s to save the town of Allensworth. Allensworth would be an historic monument and public park dedicated to the memory and spirit of Colonel Allensworth as well as a place to note the achievements and contributions of African Americans to the history and development of California. In 1976, when the town site became a state historic park, restorations began, and plans began for further preservation, restoration, and reconstruction, and for interpretation of the history of Allensworth.

References and Suggested Reading

Allensworth State Historical Park. 2012 California Dept of Parks and Recreation. 16 Jul 2012

http://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=21298